April 29, 2021 11.12am EDT

Author

- Nicholas R. LongrichSenior Lecturer in Evolutionary Biology and Paleontology, University of Bath

Disclosure statement

Nicholas R. Longrich does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Bath provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

We believe in the free flow of information

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

Republish this article

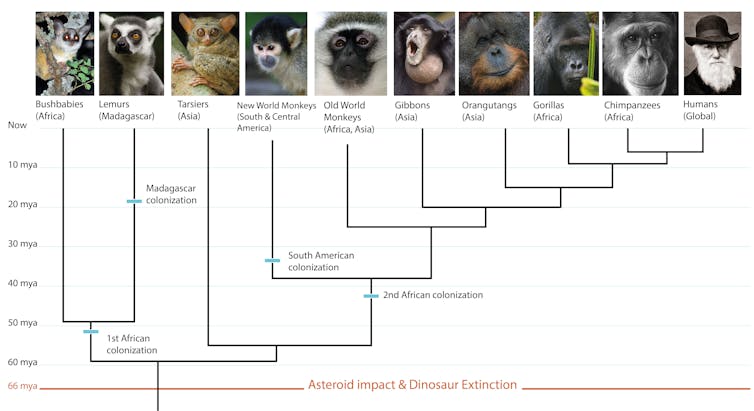

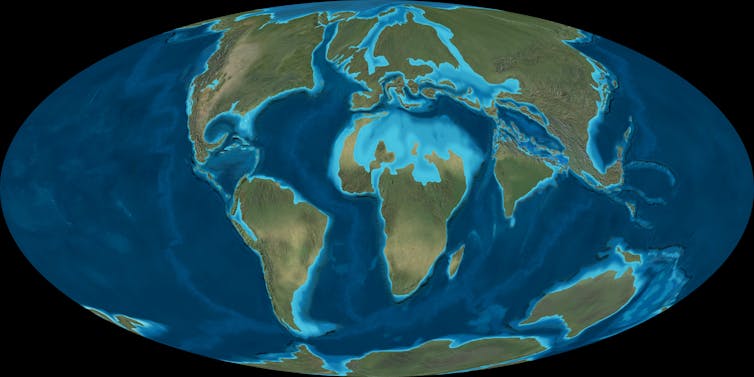

Humans evolved in Africa, along with chimpanzees, gorillas and monkeys. But primates themselves appear to have evolved elsewhere – likely in Asia – before colonising Africa. At the time, around 50 million years ago, Africa was an island isolated from the rest of the world by ocean – so how did primates get there?

A land bridge is the obvious explanation, but the geological evidence currently argues against it. Instead, we’re left with a far more unlikely scenario: early primates may have rafted to Africa, floating hundreds of miles across oceans on vegetation and debris.

Such oceanic dispersal was once seen as far-fetched and wildly speculative by many scientists. Some still support the land bridge theory, either disputing the geological evidence, or arguing that primate ancestors crossed into Africa long before the current fossil record suggests, before the continents broke up.

But there’s an emerging consensus that oceanic dispersal is far more common than once supposed. Plants, insects, reptiles, rodents and primates have all been found to colonise island continents in this way – including a remarkable Atlantic crossing that took monkeys from Africa to South America 35 million years ago. These events are incredibly rare but, given huge spans of time, such freak events inevitably influence evolution – including our own origins.

Primate origins

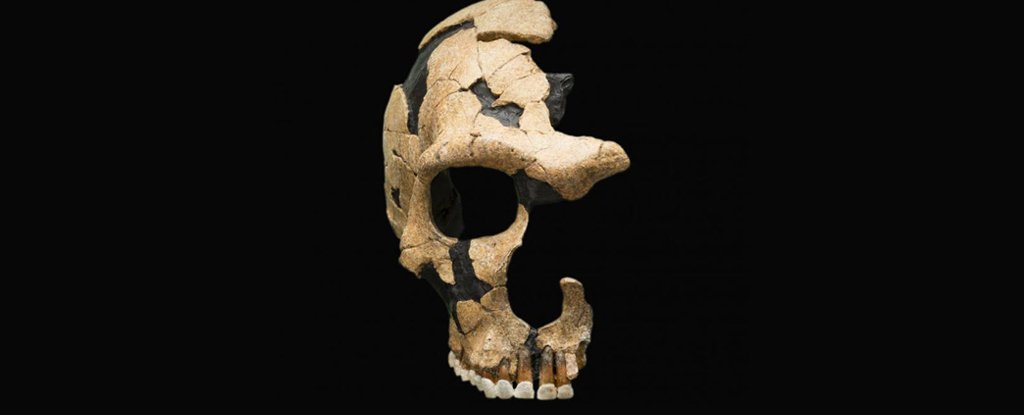

Humans appeared in southern Africa between 200,000–350,000 years ago. We know we come from Africa because our genetic diversity is highest there, and there are lots of fossils of primitive humans there.

Our closest relatives, chimps and gorillas, are also native to Africa, alongside baboons and monkeys. But primates’ closest living relatives – flying lemurs, tree shrews and rodents – all inhabit Asia or, in the case of rodents, evolved there. Fossils provide somewhat conflicting evidence, but they also suggest primates arose outside of Africa.

The oldest primate relative, Purgatorius, lived 65 million years ago, just after the dinosaurs disappeared. It’s from Montana.

The oldest true primates also occur outside Africa. Teilhardina, related to monkeys and apes, lived 55 million years ago, throughout Asia, North America, and Europe. Primates arrived in Africa later. Lemur-like fossils appear there 50 million years ago, and monkey-like fossils around 40 million years ago.

But Africa split from South America and became an island 100 million years ago, and only connected with Asia 20 million years ago. If primates colonised Africa during the 80 million years the continent spent isolated, then they needed to cross water.

Ocean crossings

The idea of oceanic dispersal is central to the theory of evolution. Studying the Galapagos Islands, Darwin saw only a few tortoises, iguanas, snakes, and one small mammal, the rice rat. Further out to sea, on islands like Tahiti, were only little lizards.

Darwin reasoned that these patterns were hard to explain in terms of Creationism – in which case, similar species should exist everywhere – but they made sense if species crossed water to colonise islands, with fewer species surviving to colonise more distant islands.

He was right. Studies have found tortoises can survive weeks afloat without food or water – they probably bobbed along until hitting the Galapagos. And in 1995, iguanas swept offshore by hurricanes washed up 300km away, very much alive, after riding on debris. Galapagos iguanas likely travelled this way.

The odds are against such crossings. A lucky combination of conditions – a large raft of vegetation, the right currents and winds, a viable population, a well-timed landfall – is needed for successful colonisation. Many animals swept offshore simply die of thirst or starvation before hitting islands. Most never make landfall; they disappear at sea, food for sharks. That’s why ocean islands, especially distant ones, have few species.

Rafting was once treated as an evolutionary novelty: a curious thing happening in obscure places like the Galapagos, but irrelevant to evolution on continents. But it’s since emerged that rafts of vegetation or floating islands – stands of trees swept out to sea – may actually explain many animal distributions across the world.

Rafting

Several primate rafting events are well established. Today, Madagascar has a diverse lemur fauna. Lemurs arrived from Africa around 20 million years ago. Since Madagascar has been an island since the time of the dinosaurs, they apparently rafted the 400 kilometre-wide Mozambique Channel. Remarkably, fossils suggest the strange aye-aye crossed to Madagascar separately from the other lemurs.

Even more extraordinary is the existence of monkeys in South America: howlers, spider monkeys and marmosets. They arrived 35 million years ago, again from Africa. They had to cross the Atlantic – narrower then, but still 1,500 km wide. From South America, monkeys rafted again: to North America, then twice to the Caribbean.

Read more: Monkey teeth fossils hint several extinct species crossed the Atlantic

But before any of this could happen, rafting events would first need to bring primates to Africa: one brought the ancestor of lemurs, another carried the ancestor of monkeys, apes, and ourselves. It may seem implausible – and it’s still not entirely clear where they came from – but no other scenario fits the evidence.

Rafting explains how rodents colonised Africa, then South America. Rafting likely explains how Afrotheria, the group containing elephants and aardvarks, got to Africa. Marsupials, evolving in North America, probably rafted to South America, then Antarctica, and finally Australia. Other oceanic crossings include mice to Australia, and tenrecs, mongooses and hippos to Madagascar.

Oceanic crossings aren’t an evolutionary subplot; they’re central to the story. They explain the evolution of monkeys, elephants, kangaroos, rodents, lemurs – and us. And they show that evolution isn’t always driven by ordinary, everyday processes but also by bizarrely improbable events.

Macroevolution

One of Darwin’s great insights was the idea that everyday events – small mutations, predation, competition – could slowly change species, given time. But over millions or billions of years, rare, low-probability, high-impact events – “black swan” events – also happen.

Read more: Black swans and other deviations: like evolution, all scientific theories are a work in progress

Some are immensely destructive, like asteroid impacts, volcanic eruptions, and ice ages – or viruses jumping hosts. But others are creative, like genome duplications, gene transfer between multicellular species – and rafting.

The role rafting played in our history shows how much evolution comes down to chance. Had anything gone differently – the weather was bad, the seas rough, the raft washed up on a desert island, hungry predators waited on the beach, no males aboard – colonisation would have failed. No monkeys, no apes – no humans.

It seems our ancestors beat odds that make Powerball lotteries seem like a safe bet. Had anything had gone differently, the evolution of life might look rather different than it does. At a minimum, we wouldn’t be here to wonder about it.

© Evans, et. al./Proceedings of the Royal Society B/Courtesy Christine Hall Researchers traced genes found in humans back to some of the earliest multicellular animals to roam Earth.

© Evans, et. al./Proceedings of the Royal Society B/Courtesy Christine Hall Researchers traced genes found in humans back to some of the earliest multicellular animals to roam Earth. © Evans, et. al./Proceedings of the Royal Society B/Courtesy Christine Hall (a,b) Kimberella quadrata (K) with frill or muscular foot (MF), proboscis (P) and associated scratch marks (SM); (c,d) Ikaria wariootia with wider end indicated by white stars and with associated trace fossil Helminthoidichnites; (e) Dickinsonia costata with white arrow indicating the direction of movement; and (f) Tribrachidium heraldicum.

© Evans, et. al./Proceedings of the Royal Society B/Courtesy Christine Hall (a,b) Kimberella quadrata (K) with frill or muscular foot (MF), proboscis (P) and associated scratch marks (SM); (c,d) Ikaria wariootia with wider end indicated by white stars and with associated trace fossil Helminthoidichnites; (e) Dickinsonia costata with white arrow indicating the direction of movement; and (f) Tribrachidium heraldicum.

An Australopithecus skull(Image: © Jose A. Bernat Bacete via Getty Images)

An Australopithecus skull(Image: © Jose A. Bernat Bacete via Getty Images)

Wildebeests have large herd sizes, but they’re not the largest animal group ever recorded.(Image: © James Warwick)

Wildebeests have large herd sizes, but they’re not the largest animal group ever recorded.(Image: © James Warwick)

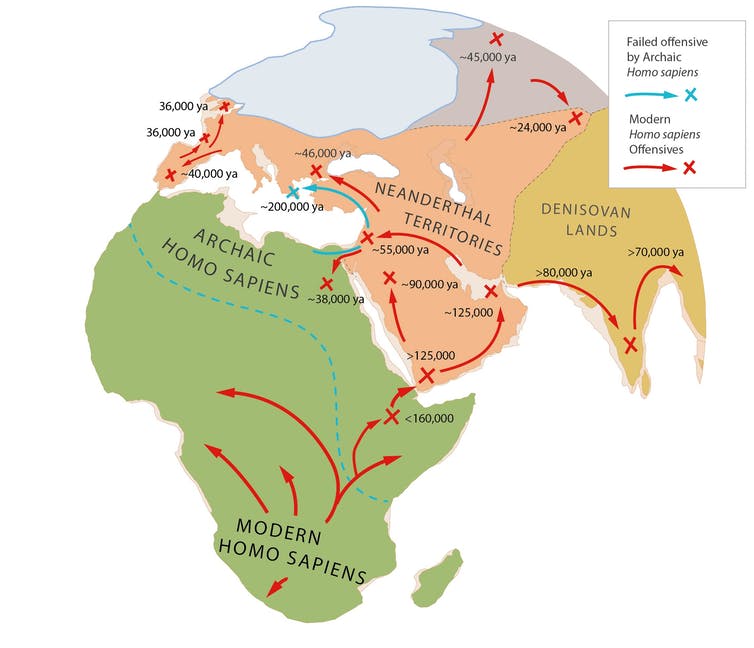

The out-of-Africa offensive. (Nicholas R. Longrich)

The out-of-Africa offensive. (Nicholas R. Longrich)