9/27/2020 8:23 AM PT

Three days later, WHO did so, stating that under certain conditions, “short-range aerosol transmission, particularly in specific indoor locations, such as crowded and inadequately ventilated spaces over a prolonged period of time with infected persons cannot be ruled out.”

Many scientists rejoiced on social media when the CDC appeared to agree, acknowledging for the first time in a September 18 website update that aerosols play a meaningful role in the spread of the virus. The update stated that COVID-19 can spread “through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks or breathes. These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways and lungs and cause infection. This is thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

However, controversy arose again when, three days later, the CDC took down that guidance, saying it had been posted by mistake, without proper review.

Right now, the CDC website does not acknowledge that aerosols typically spread SARS-CoV-2 beyond 6 feet, instead saying: “COVID-19 spreads mainly among people who are in close contact (within about 6 feet) for a prolonged period. Spread happens when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, and droplets from their mouth or nose are launched into the air and land in the mouths or noses of people nearby. The droplets can also be inhaled into the lungs.”

The site says that respiratory droplets can land on various surfaces, and people can become infected from touching those surfaces and then touching their eyes, nose or mouth. It goes on to say, “Current data do not support long range aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2, such as seen with measles or tuberculosis. Short-range inhalation of aerosols is a possibility for COVID-19, as with many respiratory pathogens. However, this cannot easily be distinguished from ‘droplet’ transmission based on epidemiologic patterns. Short-range transmission is a possibility particularly in crowded medical wards and inadequately ventilated spaces.”

Confusion has surrounded the use of words like “aerosols” and “droplets” because they have not been consistently defined. And the word “airborne” takes on special meaning for infectious disease experts and public health officials because of the question of whether infection can be readily spread by “airborne transmission.” If SARS-CoV-2 is readily spread by airborne transmission, then more stringent infection control measures would need to be adopted, as is done with airborne diseases such as measles and tuberculosis. But the CDC has told CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jonathan LaPook that even if airborne spread is playing a role with SARS-CoV-2, the role does not appear to be nearly as important as with airborne infections like measles and tuberculosis.

All this may sound like wonky scientific discussion that is deep in the weeds — and it is — but it has big implications as people try to figure out how to stay safe during the pandemic. Some pieces of advice are intuitively obvious: wear a mask, wash your hands, avoid crowds, keep your distance from others, outdoors is safer than indoors. But what about that “6 foot” rule for maintaining social distance? If the virus can travel indoors for distances greater than 6 feet, isn’t it logical to wear a mask indoors whenever you are with people who are not part of your “pod” or “bubble?”

Understanding the basic science behind how SARS-CoV-2 travels through the air should help give us strategies for staying safe. Unfortunately, there are still many open questions. For example, even if aerosols produced by an infected person can float across a room, and even if the aerosols contain some viable virus, how do we know how significant a role that possible mode of transmission is playing in the pandemic?

In contrast to early thinking about the importance of transmission by contact with large respiratory droplets, it turns out that a major way people become infected is by breathing in the virus. This is most common when someone stands within 6 feet of a person who has COVID-19 (with or without symptoms), but it can also happen from more than 6 feet away.

Viruses in small, airborne particles called aerosols can infect people at both close and long range. Aerosols can be thought of as cigarette smoke. While they are most concentrated close to someone who has the infection, they can travel farther than 6 feet, linger, build up in the air and remain infectious for hours. As a consequence, to lessen the chance of inhaling this virus, it is vital to take all of the following steps:

Indoors:

Outdoors:

Whether you are indoors or outdoors, remember that your risk increases with the duration of your exposure to others.

With the question of transmission, it’s not just the public that has been confused. There’s also been confusion among scientists, medical professionals and public health officials, in part because they have often used the words “droplets” and “aerosols” differently. To address the confusion, participants in an August workshop on airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine unanimously agreed on these definitions for respiratory droplets and aerosols:

All respiratory activities, including breathing, talking and singing, produce far more aerosols than droplets. A person is far more likely to inhale aerosols than to be sprayed by a droplet, even at short range. The exact percentage of transmission by droplets versus aerosols is still to be determined. But we know from epidemiologic and other data, especially superspreading events, that infection does occur through inhalation of aerosols.

In short, how are we getting infected by SARS-CoV-2? The answer is: In the air. Once we acknowledge this, we can use tools we already have to help end this pandemic.

PARIS – Could the mask — already seen by many scientists as the most effective shield against COVID-19 — have yet another benefit? Some researchers now believe that they expose wearers to smaller, less harmful doses of the disease that spark an immune response.

This as yet unproven theory suggests that masks could help inoculate people while we wait for a vaccine.

Nonmedical fabric or disposable masks have been recommended across the world, mainly as a way to help stop infected people from spreading the new coronavirus.

While they do not offer full protection, masks may potentially reduce the amount of virus inhaled by a wearer, according to a recent paper published this month in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

“We hypothesize that the higher a dose (or inoculum) of virus you get into your body, the more sick you get,” said one of the authors Monica Gandhi, a specialist in infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We think that masks reduce that dose of virus that you inhale and, thereby, drive up rates of asymptomatic infection.”

Gandhi, director of the UCSF-Gladstone Center for AIDS Research, said that asymptomatic infection was linked to a strong immune response from T lymphocytes — a type of white blood cell — that may act against COVID-19.

“We think masks can act as a sort of ‘bridge’ to a vaccine by giving us some immunity,” she said, adding that researchers were launching several studies to try and test the theory.

These would include looking at whether the requirement of a mask in certain cities had reduced the severity of the disease there.

They are also looking at antibody studies in Taiwan, where masks are ubiquitous but there are very few restrictions.

“Of course, it’s still a theory, but there are many arguments in its favor,” said Bruno Hoen, director of medical research at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

He said we should “take a different look at the use of masks,” which were initially deemed unnecessary by health authorities, against the backdrop of shortages.

Today, they are widely recommended to slow the spread of infection.

The theory echoes “variolation,” a rudimentary technique used before the appearance of vaccines that involved giving people a mild illness to try to inoculate them against more serious forms of a disease.

In Asia, early variolation often meant blowing dried scabs from smallpox patients up the noses of healthy people, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

When it reached Europe and America in the 18th century, the practice — which sometimes killed the patient — commonly involved inserting smallpox under the skin.

The NEJM article suggests a parallel in the idea that being exposed to small doses of virus boosts immunity.

“It is an interesting theory with a reasonable hypothesis,” said Archie Clements, Vice Chancellor Faculty of Health Sciences at Australia’s Curtin University.

But others expressed reservations.

Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University in New York, said she was “pretty skeptical of this being a good idea.”

She noted that we do not yet know if a lower dose of virus does mean a milder illness.

We do not know if masks reduce exposure to the virus, she said on Twitter, adding that the duration and level of immunity are also still poorly understood.

“This is an interesting idea, but there are too many unknowns to say that masks should be used as a tool for ‘variolating’ people against SARS-CoV-2,” she added.

A key stumbling block to answering these questions is that testing the UCSF researchers’ hypothesis is difficult.

“It is true that such a hypothesis in humans using gold standard methods (of experimental design) can never be proven given that we cannot expose humans deliberately to the virus,” Gandhi said.

But some studies have proved useful, she said, including research conducted in Hong Kong on hamsters.

Scientists simulated mask-wearing by placing one between the cages of infected rodents and healthy ones.

They found that hamsters were less likely to catch COVID-19 if they were “masked,” and even if they did catch it, their symptoms were milder.

There have also been a few accidental real-world experiments.

In one case, a cruise ship that departed from Argentina in mid-March issued everyone on board with surgical masks after the first sign of an infection.

Researchers found that 81 percent of those who caught the virus were asymptomatic, which Gandhi said compared to around 40 percent on other vessels where masks were not worn systematically.

Researchers from Stanford University examined blood samples from 28,500 patients receiving dialysis at about 1,300 facilities in 46 states in July, providing the first nationwide antibody analysis.

Researchers said dialysis patients represented an ideal population for the study because they undergo routine blood draws monthly — presenting few pandemic-related challenges. Additionally, COVID-19 risk factors “are the rule rather than the exception in the US dialysis population,” researchers said.

“We were able to determine — with a high level of precision — differences in seroprevalence among patient groups within and across regions of the United States, providing a very rich picture of the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak that can hopefully help inform strategies to curb the epidemic moving forward by targeting vulnerable populations,” lead author Shuchi Anand, director of the Center for Tubulointerstitial Kidney Disease at Stanford University, said in a press release.

Levels of antibodies averaged greater than 25% in the Northeast, while the western U.S. saw an average of less than 5%, according to the study.

Accounting for age, sex, race, ethnicity and religion around the country, researchers estimated that 9.3% of the U.S. population has antibodies. Comparing their data to research from Johns Hopkins University, the study authors estimated that only 9.2% of patients with antibodies were previously diagnosed with COVID-19.

Researchers found that residents of mostly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods were two to four times more likely to test positive for antibodies. People living in lower-income areas were two times more likely, and people living in densely populated areas were ten times more likely.

The results approximately match data announced this week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Speaking during a Senate hearing, CDC Director Robert Redfield said that about 90% of Americans are still susceptible to the virus.

Redfield emphasized that people should continue to wear masks, social distance and stay home, since most people are still vulnerable. He said the CDC plans to release its study in the next week.

Experts say some level of so-called “herd immunity” — when enough of the population has immunity that the virus can no longer spread effectively — will not be achieved until a substantial number of people have access to a coronavirus vaccine.

Let’s face it: No one enjoys having a mask cover half their face.

They can be scratchy, sweaty, stuffy — all reasons why people quickly ditch them on a restaurant patio, avoid wearing them around friends and family or “forget” them while dashing into a store.

But experts warn that at this point in the pandemic, when the benefits of mask-wearing are growing clear — and COVID-19 cases are rising rapidly, with hospitalizations and deaths expected to follow — Canadians should be donning their masks more, not less.

“Keep wearing your mask, as much as you can, especially with people you don’t live with,” Toronto’s medical officer of health, Dr. Eileen de Villa, stressed on Monday.

Multiple experts who spoke to CBC News this week say that means keeping a mask on in a variety of settings, even if local bylaws don’t mandate it.

“People think their private residences are exempt from the science of COVID-19 and don’t have that transmission risk,” said Dr. Zain Chagla, an associate professor of medicine at McMaster University and an infectious disease consultant at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton.

“As we keep talking about, a lot of this jump and surge is actually due to transmission in some private residences.”

Family outings, cottage gatherings and a barbecue in a park have all sparked multiple cases of infections, according to public health officials in different Ontario cities.

Edmonton-based health policy expert Timothy Caulfield agreed that people should strive to wear a mask around anyone from outside someone’s own household.

“If it’s an indoor environment and you can’t get that good two-metre space all the time, think about wearing a mask — even if it’s family members,” said Caulfield, Canada Research Chair in health law and policy and research director of the Health Law Institute at the University of Alberta.

So what about outdoors? Many people don’t bother with masks outside, since there’s consensus that outdoor spaces are far less risky for virus transmission when compared with indoor settings, thanks to the constant flow of fresh air.

But Chagla said masks could be helpful in any crowded outdoor space where staying a couple of metres apart is challenging — “even if you’re on the patio, until you have to eat and drink, and then putting it back on afterwards,” he said. “We just have to kind of get people to make it a reflex.”

The advice to wear a mask in so many settings might be a confusing message after a stretch of shifting guidelines.

In the early days of the pandemic, there was scant evidence showing how helpful masks could be at reducing transmission of the new, and little-understood, SARS-CoV-2 virus.

More recently, studies have shown that masks reduce the rate at which sick people shed the virus and the distance droplets travel from your mouth.

Research on non-medical masks from a team at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for example, found that many masks — and particularly those with multiple layers — are able to block a high number of droplets from getting through the fabric.

While the lab-based findings don’t provide a perfect look at how virus transmission works in the real world, there’s been growing consensus among Canadian public health officials that masks are a key tool for curbing the spread.

For months, face coverings have been an official recommendation from the federal government for times when physical distancing isn’t possible.

Mandatory mask bylaws for various public spaces have also popped up in cities across the country, from the small Montreal suburb of Côte Saint-Luc to Ontario’s largest cities, Toronto and Ottawa.

A growing number of Canadians also back that push.

More than 80 per cent now support governments ordering people to wear a mask in all indoor spaces, noted a recent online survey by Leger and the Association for Canadian Studies released on Tuesday.

Even more respondents — 87 per cent — said wearing a mask is a civic duty because it protects others from COVID-19.

WATCH | Quebecers disobeying mask rules will be fined, premier says:

Quebec Premier François Legault says ‘irresponsible’ citizens will face fines if they refuse to wear masks where it’s mandatory. 1:07

While Canadians have largely embraced mask-wearing at spots like grocery stores and other crowded public spaces, experts worry the practice is less common behind closed doors, whether at a private backyard gathering or inside a restaurant.

“The concept still holds true for gatherings at one’s own house and some of those other establishments where you can’t wear a mask all the time,” Chagla said.

“You probably should be wearing the mask — most of the time — in those establishments.”

Dr. Anna Banerji, an infectious disease expert and faculty lead for Indigenous and refugee health at the University of Toronto, also stressed the need for patrons at restaurants, bars and shops to make more effort to protect workers.

“Because it’s not just the consumers, it’s the people that also work in the stores where they are being exposed to many different people,” she said. “If all these people are coming in and not wearing masks or wearing them below their nose, that puts these people at risk.”

Caulfield said masks remain “just one tool” to reduce the risk of transmission, alongside other basic precautions like hand-washing and keeping at least a two-metre distance from anyone outside your household.

It’s a message that comes as Canada’s chief public health officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, said the country is at a “crossroads” amid a surge of new COVID-19 cases.

“If you manage to reduce those contacts and make some choices of not going to big gatherings and some of these social events,” she warned this week, “you can manage this without a lockdown.”

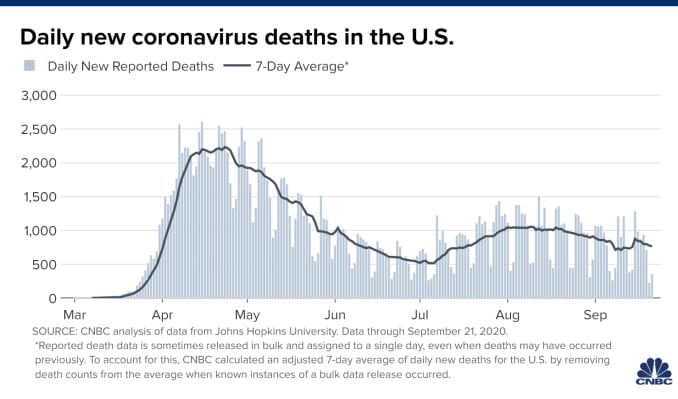

The coronavirus, which was first confirmed in the United States about eight months ago, has killed more than 200,000 people across the country as of Tuesday as U.S. officials rush to approve and manufacture a vaccine.

The U.S. had reported at least 200,005 confirmed Covid-19 deaths as of mid-day Tuesday, more than any other country in the world, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

The U.S., which accounts for roughly 21% of all confirmed Covid-19 deaths around the world despite having only 4% of the world’s population, is battling one of the deadliest outbreaks in the world. Fatalities in the U.S. have doubled over the last four months, after the virus took 100,000 lives in the first four months of the outbreak.

Coronavirus deaths have now outpaced the number of American soldiers lost during World War I and the Vietnam War combined, according to the Census Bureau.

The U.S. has reported about 61.09 deaths per 100,000 residents, making it the country with the 11th most deaths per capita, according to data from Hopkins. Brazil, Chile, Spain, Bolivia, Peru and the United Kingdom among others have all reported more deaths per capita than the U.S., according to Hopkins data.

The virus has disproportionately killed people with underlying health conditions, such as obesity and asthma, and people who are older, according to data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The virus has also disproportionately infected and killed Black and Hispanic people, as well as Native Americans, the CDC says.

The U.S. continues to report worryingly high numbers of new confirmed cases and deaths every day. Over the past seven days, the country has reported an average of more than 43,300 new cases per day, up over 19% compared with a week ago, according to a CNBC analysis of Hopkins data. And the country continues to report more than 750 Covid-19 deaths every day. While doctors have new medications and treatment strategies to save the lives of Covid-19 patients, epidemiologists worry deaths could accelerate if the virus surges in the winter as expected.

“The worst is yet to come. I don’t think perhaps that’s a surprise, although I think there’s a natural tendency as we’re a little bit in the Northern hemisphere summer, to think maybe the epidemic is going away,” Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, said earlier this month.

IHME previously forecast that the U.S. would report more than 410,000 Covid-19 deaths by Jan. 1 due to the prospect of a “deadly December.” The modeling group has since revised down its estimate, driven by “steeper than expected declines seen in deaths” in several states. The group now projects that the U.S. will reach 378,000 deaths by the new year.

“Not only are these real people, but these are families that are suffering because they’ve lost loved ones, or they’re dealing with a loved one that has long-term health issues because of Covid-19,” said Dr. Syra Madad, senior director of the systemwide special pathogens program at New York City Health + Hospitals. “We’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg. We’re only nine months into this pandemic.”

Looking at deaths alone, though, provides an incomplete picture of the true toll of the pandemic, Madad said, because researchers are only just beginning to learn about the long-term health complications that Covid-19 causes. She added that the death toll of 200,000 likely underestimates the total number of deaths caused either directly or indirectly by Covid-19.

Excess deaths studies, which compare projections based on historical death statistics with the number of actual deaths, seek to capture a more encompassing picture of the Covid-19 fatality count. The CDC currently estimates more than 200,000 excess deaths in the U.S. since Feb. 1.

“I do believe that the true number of deaths associated with Covid-19 is much, much higher,” Madad said, adding that New York City is testing the bodies of people who have died over the past few months to best capture the Covid-19 death toll. She said this data will help researchers understand the virus.

Madad acknowledges that policymakers in New York state, which accounts for more than 16% of total deaths in the U.S., made mistakes when the region was hit hard in mid-March by the virus.

“New York City sort of set the example for the rest of the nation of what to avoid and lessons learned,” she said. The U.S. has implemented a patchwork response to the pandemic and while some states have improved upon New York’s initial response, others haven’t, she added. The U.S., she said, is playing a game of “whack-a-mole” when it comes to stopping outbreaks.

“Pandemics are inevitable. They’re going to happen. But does it have to get this bad? No,” Madad said. “That was avoidable, and we’ve made significant mistakes as a nation. We have been behind the eight ball from the very beginning.”

As New York began to bring its outbreak under control, the virus surged elsewhere. This summer, the virus tore through much of America’s Sun Belt, including some of the country’s most populous states such as Florida, Texas, Arizona and California. At one point earlier this summer, those four states accounted for more than half of all new cases confirmed in the U.S. As of Friday, they accounted collectively for 24.5% of all new cases, according to Hopkins data.

“We are seeing the number of cases and hospitalizations come down,” said Catherine Troisi, an infectious disease epidemiologist at UTHealth School of Public Health in Houston, adding that the decline has been slow. “It’s been coming down, but we’re certainly not at the levels we were back in April.”

The Texas Department of State Health Services has reported more than 698,300 cases of the virus and over 14,900 Covid-19 deaths. With new cases off the state’s peak, the governor is moving forward with reopening more businesses, including retail stores, gyms and restaurants.

Troisi said she’s concerned about the reopening plans, especially as she continues to examine the data for signs of a post-Labor Day surge. She added that the reopening might send the wrong message, suggesting to the public that the virus is no longer a threat. She said if the public fails to continue to adhere to public health protocol and if state policymakers don’t prioritize the pandemic response, the virus is a looming threat that could again overwhelm hospitals in the state.

“We absolutely, positively could have done better. There have been mistakes all along the way, and we’re still making some mistakes,” she said, adding that there is mixed messaging at the national and state level. “Could we have prevented all of those deaths? No, especially in the early stages, and even now, I’m sure, there are some deaths that can’t be prevented. But we could have prevented a great deal of them had the government acted quicker and if we had a national strategy, if we had not disinvested in public health.”

From the wave of outbreaks across the Sun Belt, the virus has now migrated again and appears to be spreading most rapidly in parts of the Midwest.

“Slowly over time [the virus] has spread out across the country,” said Christine Peterson, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the University of Iowa. “And we’re now at a point where it really seems to be the middle delta of the country that’s hardest hit for various reasons. The Northern Central Plains down into Iowa and Missouri and Arkansas, all seem to be having a lot more cases now.”

Iowa reported 597 new cases on Tuesday, but its seven-day average stands at 849, an increase of more than 32% compared with a week before, according to CNBC’s analysis of Hopkins data. Peterson said communities that have endured a major outbreak are more likely to comply with public health measures. But it’s unfortunate, she added, that parts of the country that avoided an early epidemic haven’t learned from what’s happened in other parts of the country.

In Iowa City, where Peterson is based, bars remained open until just a few weeks ago and weren’t closed until well after cases began to spike, she said. She added that much of the rise in new cases across the Midwest can likely be traced back to university reopenings.

″[Universities] brought people from around the state to a central location,” she said. “And their perceived risk was a lot lower, which meant that there were a lot of people hanging out in bars and parties, and that led to a lot of rapid spread within this community.”

She added that the spike in cases over the past few weeks is beginning to turn up in the daily death toll.

“We have flipped from having a moderate increase in our above-normal death rate to being significantly over.”

Play

Duration02:07Toggle MuteVolume

Toggle Fullscreen

The document said person-to-person and coughing/sneezing/breathing are the primary ways the virus is transmitted through droplets, but the agency then said there is growing evidence that airborne droplets after a sneeze or cough — droplets that linger in the air — are of concern.

“There is growing evidence that droplets and airborne particles can remain suspended in the air and be breathed in by others, and travel distances beyond 6 feet (for example, during choir practice, in restaurants, or in fitness classes),” the document said. “In general, indoor environments without good ventilation increase this risk.”

But on Monday, the agency removed the mention of airborne transmission from their website with the following explanation.

“A draft version of proposed changes to these recommendations was posted in error to the agency’s official website,” it reads. “CDC is currently updating its recommendations regarding airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). Once this process has been completed, the update language will be posted.”

In a Zoom conference call on Monday, a senior CDC official explained that the online post that suggested the virus that causes COVID-19 is airborne was an early draft still undergoing scientific review and was posted by mistake.

John Brooks, the chief medical officer for CDC’s COVID-19 response, apologized.

“I just want to let you know that this early draft of a document that’s presently undergoing scientific review wasn’t intended to be posted,” he said. “That was an error on behalf of our agency, and I apologize on behalf of CDC for that. We weren’t ready to put it up.”

Brooks said that it remains unclear if the virus is airborne.

“We’re looking at possibility of COVID being transmitted as sort of an opportunistic airborne condition,” he said. “That means that…it can possibly be transmitted through the airborne route, but that this is not the main mode of transmission. The main mode of transmission remains close exposure within that six foot circumference of a person is effective.”

Brooks also defended what he called a “rigorous scientific review process” by the CDC of its scientific studies “to ensure timely, accurate, reliable, the most important trustworthy public health information and recommendations.”

“CDC as an agency stands by the scientific integrity (of) the more than hundred — now over one hundred — COVID-19 reports that the MWWR war has published to date,” he said.

The career of the coronavirus so far is, in Darwinian terms, a great success story.

By

Mr. Quammen is the author of “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic.”

No sensible person can dispute that Covid-19 is a great tragedy for humanity — a tragedy even in the ancient Greek sense, as defined by Aristotle, with the disastrous ending contingent on some prideful flaw in the protagonist. This time it’s not Oedipus or Agamemnon. This time it’s we who are that cocky protagonist, having brought disaster on ourselves. The scope and the devastation of the pandemic reflect bad luck, yes, and a dangerous world, yes, but also catastrophic failures of human foresight, communal will and leadership.

But look past that record of human failures for a moment, and consider this whole event from the point of view of the virus. Measure it by the cold logic of evolution: The career of SARS-CoV-2 so far is, in Darwinian terms, a great success story.

This now-notorious coronavirus was once an inconspicuous creature, lurking quietly in its natural host: some population of animals, possibly bats, in the caves and remnant forests of southern China. The existence of such a living hide-out — also known as a reservoir host — is logically necessary when any new virus appears suddenly as a human infection.

Why? Because everything comes from somewhere, and viruses come from cellular creatures, such as animals, plants or fungi. (A viral particle isn’t a cell; it’s just a strip of genomic instructions enclosed in a protein capsule — a message in a bottle.) A virus can only replicate itself, function as though it were alive and abide over time if it inhabits the cells of a more complex creature, like a sort of genetic parasite.

Generally, the relationship between virus and reservoir host represents an ancient evolutionary accommodation. The virus persists at a low profile, without causing trouble, without proliferating explosively, and in return it gets long-term security. Its horizons are modest: relatively small population, limited geographical scope.

But this guest-host arrangement is not imperturbably stable, or the end of the story. If another sort of creature comes in close contact with the host — by preying on it, by capturing it or maybe only by sharing the same cave — the virus might be jostled from its comfort zone and into a new situation: a new potential host.

Suddenly it’s like a gaggle of rats that jump ashore from a ship onto a remote island. The virus might thrive in this new habitat, or it might fail and die out. If it happens to thrive, if by chance it finds the new situation hospitable, then it might establish itself not just in the first new individual but in the new population.

It might discover itself capable of entering some of the new host’s cells, replicating abundantly and getting itself transmitted from that individual to others. That jump is called host-switching or, by a slightly more vivid term, spillover. If the spillover results in disease among a dozen or two dozen people, you have an outbreak. If it spreads countrywide, an epidemic. If it spreads worldwide, a pandemic.

Imagine again that gaggle of rats on a previously rat-free island. To their delight, they find the island inhabited by several endemic species of birds, naïve and trusting, accustomed to laying their eggs on the ground. The rats eat those eggs. Soon the island has lost its terns and its rails and its dotterels, but it has an abundance of rats.

If the remote island of habitat is a human being newly colonized by a virus from a nonhuman animal, we call that virus a zoonosis. The resulting infection is a zoonotic disease. More than 60 percent of human infectious diseases, including Covid-19, fall into this category of zoonoses that have succeeded. Some zoonotic diseases are caused by bacteria (such as the bacillus responsible for bubonic plague) or other kinds of pathogen, but most are viral.

Viruses have no malice against us. They have no purposes, no schemes. They follow the same simple Darwinian imperatives as do rats or any other creature driven by a genome: to extend themselves as much as possible in abundance, in geographical space and in time. Their primal instinct is to do just what God commanded to his newly created humans in Genesis 1:28: “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it.”

For an obscure virus, abiding within its reservoir host — a bat or a monkey in some remote region of Asia or Africa, or maybe a mouse in the American Southwest — spilling over into humans offers the opportunity to comply. Not every successful virus will “subdue” the planet, but some go a fair way toward subduing at least humans.

This is how the AIDS pandemic happened. A chimpanzee virus now known as SIVcpz passed from a single chimp into a single human, possibly by blood contact during mortal combat, and took hold in the human. Molecular evidence developed by two teams of scientists, one led by Dr. Beatrice H. Hahn, the other by Michael Worobey, tells us that this most likely happened more than a century ago, in the southeastern corner of Cameroon, in Central Africa, and that the virus took decades to attain proficiency at human-to-human transmission.

By 1960 that virus had traveled downriver to big cities such as Léopoldville (now Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo); then it spread to the Americas and burst into notice in the early 1980s. Now we call it “H.I.V.-1 group M”: It’s the pandemic strain, accounting for most of the 71 million known human infections to date.

Chimpanzees were a species in decline, alas, because of habitat loss and killing by humans; humans were a species in ascendance. The SIVcpz virus reversed its own evolutionary prospects by getting into us and adapting well to the new host. It jumped from a sinking lifeboat onto a luxury cruise ship.

SARS-CoV-2 has done likewise, though its success has occurred much more quickly. It has now infected more than 30 million people, just under half as many as the number of people infected by H.I.V., and in 10 months rather than 10 decades. It’s not the most successful human-infecting virus on the planet — that distinction lies elsewhere, possibly with the Epstein-Barr virus, a very transmissible species of herpesvirus, which may reside within at least 90 percent of all humans, causing syndromes in some and lying latent in most. But SARS-CoV-2 is off to a roaring start.

Now, for purposes of illustration, imagine a different scenario, involving a different virus. In the mountain forests of Rwanda lives a small, insectivorous bat known as Hill’s horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hilli). This bat is real, but it has been glimpsed only rarely and is classified as critically endangered. Posit a coronavirus, for which this bat serves as reservoir host. Call the virus RhRW19 (a coded abbreviation of the sort biologists use), because it was detected within the species Rhinolophus hilli (Rh), in Rwanda (RW), in 2019 (19).

The virus is hypothetical, but it’s plausible, given that coronaviruses are known to occur in many kinds of horseshoe bats around the world. RhRW19 is on the brink of extinction, because the rare bat is its sole refuge. The lifeboat is leaking badly and nearly swamped.

But then a single Rwandan farmer, needing fertilizer for his crops on a meager patch of dirt, enters a cave and shovels up some bat guano. The guano has come from Hill’s horseshoe bats and it contains the virus. In the process of shoveling and breathing, the farmer becomes infected with RhRW19. He passes it to his brother, and the brother carries it to a provincial clinic where he works as a nurse. The virus circulates for weeks among employees of the clinic and their contacts, making some sick, killing one person, while natural selection improves its capacity to replicate within cells of the human respiratory tract and transmit between people.

A visiting doctor becomes infected, and she carries the virus back to Kigali, the capital. Soon it is at the airport, in the airways of people who don’t yet feel symptoms and are boarding flights for Kinshasa, Doha and London. Now you can give the improved virus a different name: SARS-CoV-3. It’s a success story that hasn’t happened yet but very easily could.

Coronaviruses are an exceptionally dangerous group. The journal Cell recently published a paper on pandemic diseases and how Covid-19 has come upon us, by a scientist named Dr. David M. Morens and one co-author. Dr. Morens, a prolific author and keen commentator, serves as senior scientific adviser to the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci. His co-author on this paper is Dr. Fauci.

ADVERTISEMENT

The paper says, among other things, that coronaviruses harbored in various mammalian species “may essentially be preadapted to human infectivity.” Not just bats but other mammals — pangolins, palm civets, cats, ferrets, mink, who knows what — contain cells that are susceptible to the same viral hooks that allow coronaviruses to catch hold of some human cells. Existing within those reservoir hosts may prepare the viruses nicely for infecting us.

The closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 is a virus discovered seven years ago, in a bat captured at a mine shaft in Yunnan Province, China, by a team under the leadership of Dr. Zhengli Shi, of the Wuhan Institute of Virology. This virus carries the moniker RaTG13. It is about 96 percent similar to SARS-CoV-2, but that four percentage point difference represents decades of evolutionary divergence, possibly in a different population of bats. In other words, RaTG13 and our nemesis bug are not the same virus; they are like cousins who have lived all their adult lives in separate towns.

What happened, during those decades of evolutionary divergence, to bring a still-undiscovered bat coronavirus to the brink of spillover into humans and enable it to become SARS-CoV-2? We don’t yet know. Scientists in China will keep looking for that closer-match virus. The evidence gathered so far is mixed and incomplete, complicated by the fact that coronaviruses are capable of a nifty evolutionary trick: recombination.

That means that when two strains of coronavirus infect the same individual animal, they may swap sections and emerge as a composite, possibly (by sheer chance) encompassing the most aggressive, adaptive sections of the two. SARS-CoV-2 may be such a composite, built by happenstance and natural selection from components known to exist among other viruses in the wild, and emerging from its nonhuman host with a fearsome capacity to grab, enter and replicate within certain human cells.

Bad luck for us. But evolution is not rigged to please Homo sapiens.

SARS-CoV-2 has made a great career move, spilling over from its reservoir host into humans. It already has achieved two of the three Darwinian imperatives: expanding its abundance and extending its geographical range. Only the third imperative remains as a challenge: to perpetuate itself in time.

Will we ever be rid of it entirely, now that it’s a human virus? Probably not. Will we ever get past the travails of this Covid-19 emergency? Yes.

Dr. Morens has recently been a co-author of another paper examining how coronaviruses have come at us. In it, he and his colleagues nod to the eminent molecular biologist Joshua Lederberg, a Nobel Prize laureate in 1958, at age 33, who later wrote: “The future of humanity and microbes likely will unfold as episodes of a suspense thriller that could be titled ‘Our Wits Versus Their Genes.’ ”

Kaporos is, in effect, the largest live animal wet market in the country and the only one in which the customers handle the animals before the animals are killed. Many of the animals have compromised immune systems and show signs of respiratory disease. The chickens make each other sick, and they also infect some of the people who handle them with e. Coli and campylobacter. If the viruses that these animals carry commingle and mutate into a more dangerous strain that could be spread among humans, then these Kaporos wet markets could be the source of the another zoonotic disease outbreak. According to a toxicologist who studied fecal and blood samples taken during Kaporos, the ritual “constitutes a dangerous condition” and “poses a significant public health hazard.”

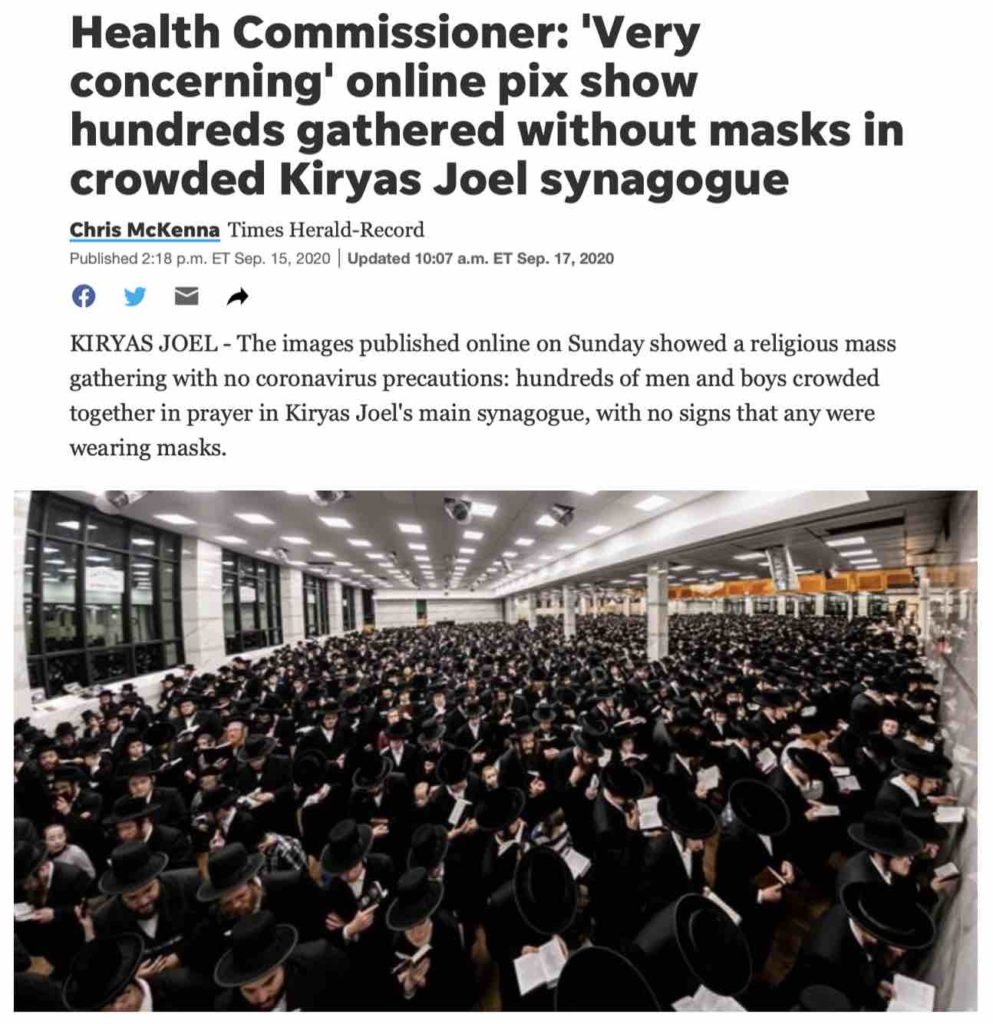

During Kaporos, tens of thousands of Hasidic Jews purchase and physically handle live animals, without PPE, putting themselves and the public at risk of zoonotic disease

In addition to putting all of us at risk of another zoonotic disease pandemic, Kaporos, which attracts hordes of people in small areas, could be a COVID “super spreader” event because Hasidic communities have been observed not wearing masks or engaging in social distancing.

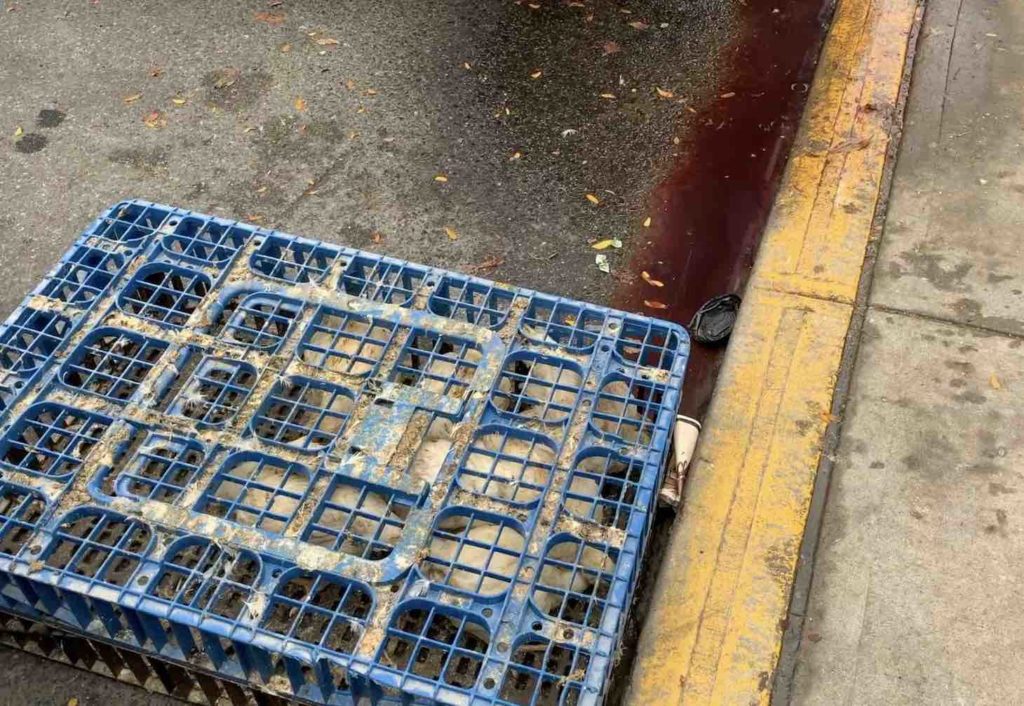

The Kaporos wet market contaminates the public streets and sidewalks of several NYC neighborhoods with the blood, feces and body parts of thousands of animals killed in pop up slaughterhouses erected without permits in violation of 8 NYC health laws

During Kaporos, some of the live and dead chickens are discarded onto the streets. Rescuers bring the survivors who they find to veterinarians and sanctuaries to live out their lives in peace

For the past several years, animal rights and public health advocates have pled with Mayor de Blasio and his revolving door of health commissioners (Dr. Mary Bassett, Dr. Oxiris Barbot and now Dr. Dave Chokshi) to shut down Kaporos, given the health code violations and the risks to the public health. Both in court and in the media, city attorneys and spokespeople for the NYC Department of Health have defended Kaporos and argued that the City has discretion over which laws to enforce. Throughout the month of September, the Alliance to End Chickens as Kaporos plastered 300 posters around New York City to sound the alarm about Kaporos.